Ottawa University, Kansas

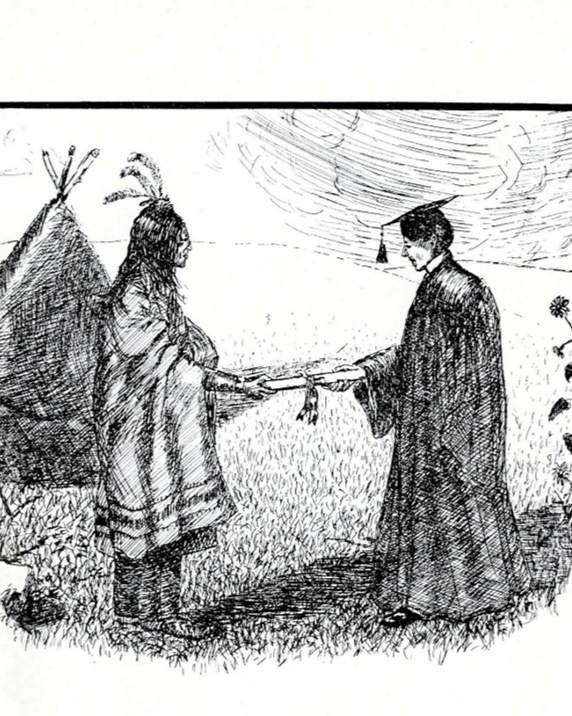

First page of The Ivy Leaf yearbook (1902). While acknowledging Ottawas aided in the founding of OU, this visual obscures Ottawa dispossession and the failure of OU to serve Ottawa students in the early 20th century.

Ottawa University, Kansas

(1865-pres)

Ottawa University was established in 1865 in Franklin County, Kansas, as a result of the 1862 treaty between the Ottawa Tribe and the United States. In that treaty, Ottawa leaders, seeking to preserve their community and avoid forced removal from Kansas, set aside 20,000 acres of their 74,000-acre reservation as a permanent endowment for a school “for the benefit of said Ottawas.” Four Ottawa leaders—James Wind, William Hurr, Joseph Badger King, and Tauy Jones—were named among the founding trustees, and the treaty guaranteed that Ottawa children and their descendants would have the right to attend the institution in perpetuity.

Soon after the school’s founding, federal officials and white school trustees misappropriated much of the land and funds designated for Ottawa education. Due this dispossession and the theft of Ottawa allotments, tribal leaders negotiated an 1867 treaty to vacate Kansas and move to a new reservation in Indian Territory. Tribal leaders, however, safeguarded their access to Ottawa University through the treaty. The treaty declared that Ottawa youth would continue to be able to attended the school with the “rights and privileges to continue so long as any children of the tribe shall present themselves for their exercise.”

Despite the clear promises of the 1862 and 1867 treaties, Ottawa University failed to fulfill its obligation to educate Ottawa youth. By 1869, much of the 20,000 acres the tribe had endowed for the school had been sold, yet the Ottawa had received only a few months of schooling in return. Ottawa leaders attempted to reclaim authority by forming a new Board of Trustees, and they argued that the existing board had been installed without their consent. The dispute resulted in two competing boards and eventually moved into federal litigation. In 1873, however, Congress intervened through a commission that sided with the white-controlled board. The commission ruled that the Ottawa had no claim to the university lands. In the decades that followed, Ottawa students were effectively barred from attending the institution founded for their benefit, and the Ottawas derived almost no educational advantage from the land endowment originally intended to support their children in perpetuity.

Throughout the 20th century, the Ottawas passed down oral accounts of this dispossession. In the 1970s, tribal leaders drew on these traditions to reestablish a relationship with the university. Beginning in 1974, Ottawa University and the Ottawa Tribe negotiated scholarship opportunities for tribal members and renewed formal ties. The relationship expanded in the early 21st century. Today, the Chief of the Ottawa Tribe holds a voting seat on the university’s Board of Trustees, and the university publicly acknowledges its origins and ongoing responsibilities to the Ottawa people.