Removal From Ohio

Removal From Ohio

(1832, 1837, 1839)

By the 1820s, the Ottawa land base in Ohio had been so dramatically reduced that many Ottawa relied on debts incurred with traders for their subsistence. Alcohol was pushed on Ottawas by local merchants, and settlers desiring payment or lands demanded Ottawa removal. Despite these dire circumstances of life, Ottawas resisted removal.

Ottawa villages along the Maumee, including Roche de Boeuf, Blanchard's Fork, and Oquanoxie's Village, sharply divided over the efficacy of removal. Although the villages negotiated with the federal government as separate entities, all Ottawa villages along the Maumee River ultimately suffered expulsion from their historic homelands. An 1831 Treaty, signed by President Andrew Jackson, dictated that the Ottawas residing at Blanchard's Fork and Oquanoxie's Village remove to a reservation of 34,000 acres along the Marais des Cygnes River in what would later become Franklin County, Kansas. The treaty granted the Ottawa the land “in fee simple.” In the same treaty, the Ottawas residing nearby at the village of Roche de Boeuf were to remove later and to receive 40,000 acres in an adjoining reservation, with the same protections granted to their reserve. Some Ottawas fled to Walpole Island in Canada, or lingered, landless, in Ohio for a time, but most Ottawas residing along Maumee River were moved west in the 1830s.

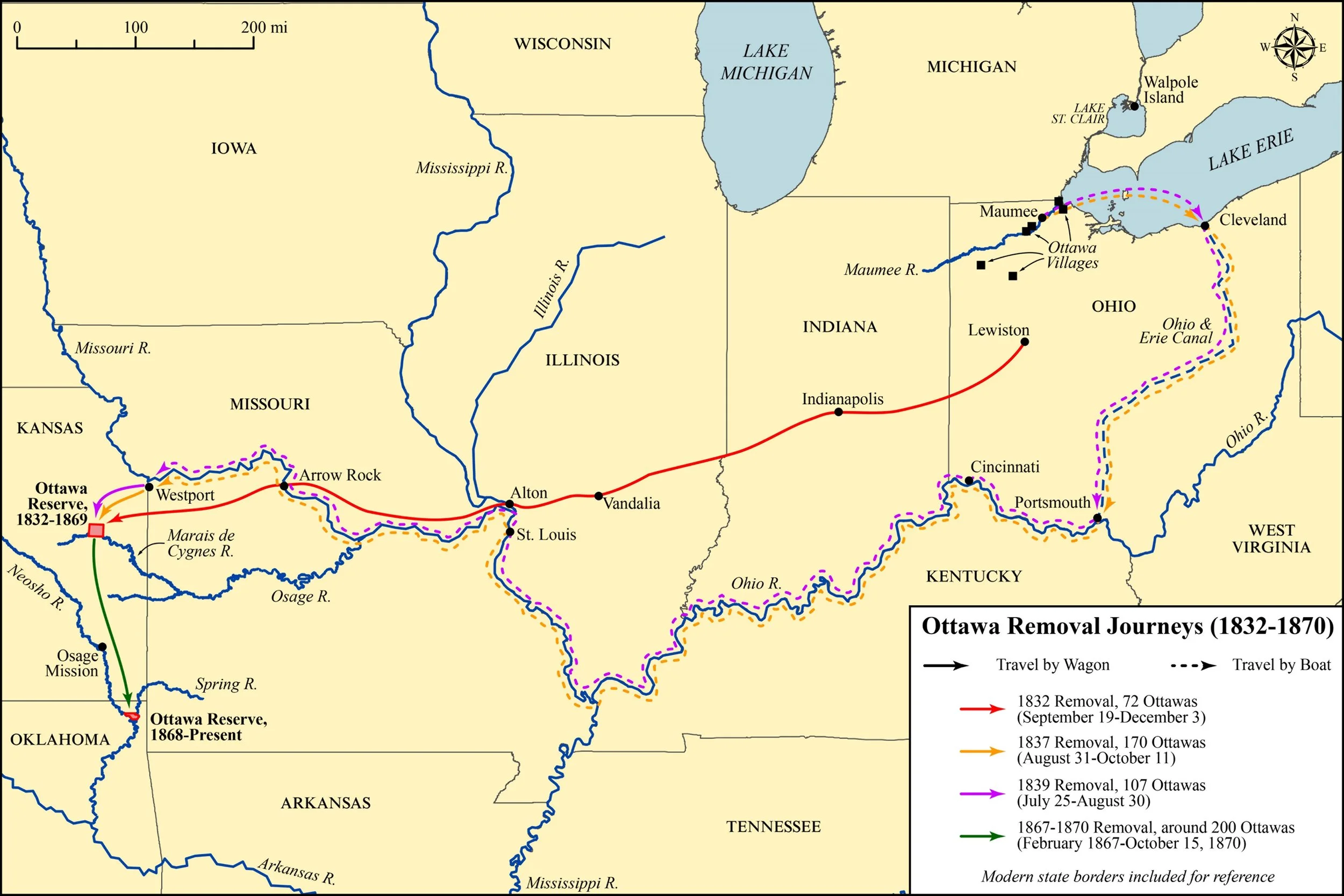

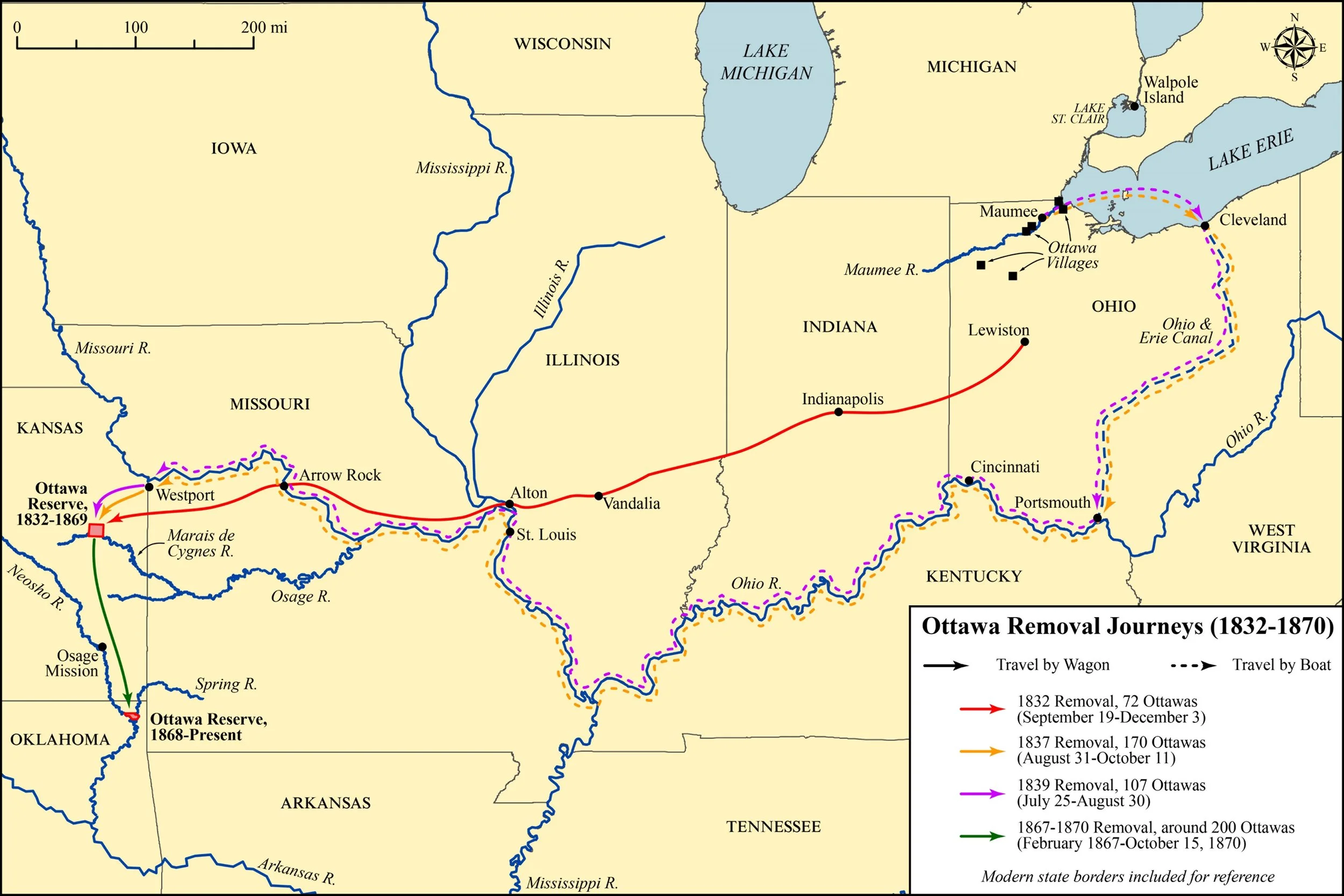

Removal from Ohio in the 1830s took place in three separate journeys—one by land and two others mostly by boat. The 1832 journey from Ohio was by land, and those Ottawas were under the leadership of Chief O-que-nox-cey. This first group also appears to have included Commechaw, who would later become an Ottawa chief. This trip was a harrowing winter journey the Ottawas made alongside a group of Shawnees and Senecas also being removed from Ohio.

The 1837 journey was under the leadership of Wau-soin-oquette, a son of Otusa and grandson of Pontiac. This group also appears to have included Lewis King (Pe-mat-se-win) and his children, including future chief Joseph Badger King. Joseph Badger King records his remembrances of this journey in an oral history conducted in 1913. Finally, the 1839 journey was under the leadership of Au-to-kee, a grandson of Pontiac, and his half-brother Notino (listed as No-tan-o on the removal roll) also made the journey at this time.

Only a small handful died on the trips themselves, but a large proportion of the Ottawa died in the years that followed. Within a few years of removal, around half of the roughly 500 Ottawas who had left Ohio for Kansas died of illness, malnutrition, and exposure. As a result, the formerly separate village bands consolidated into one community for strength.