Removal From Kansas

Removal From Kansas

(1867-1870)

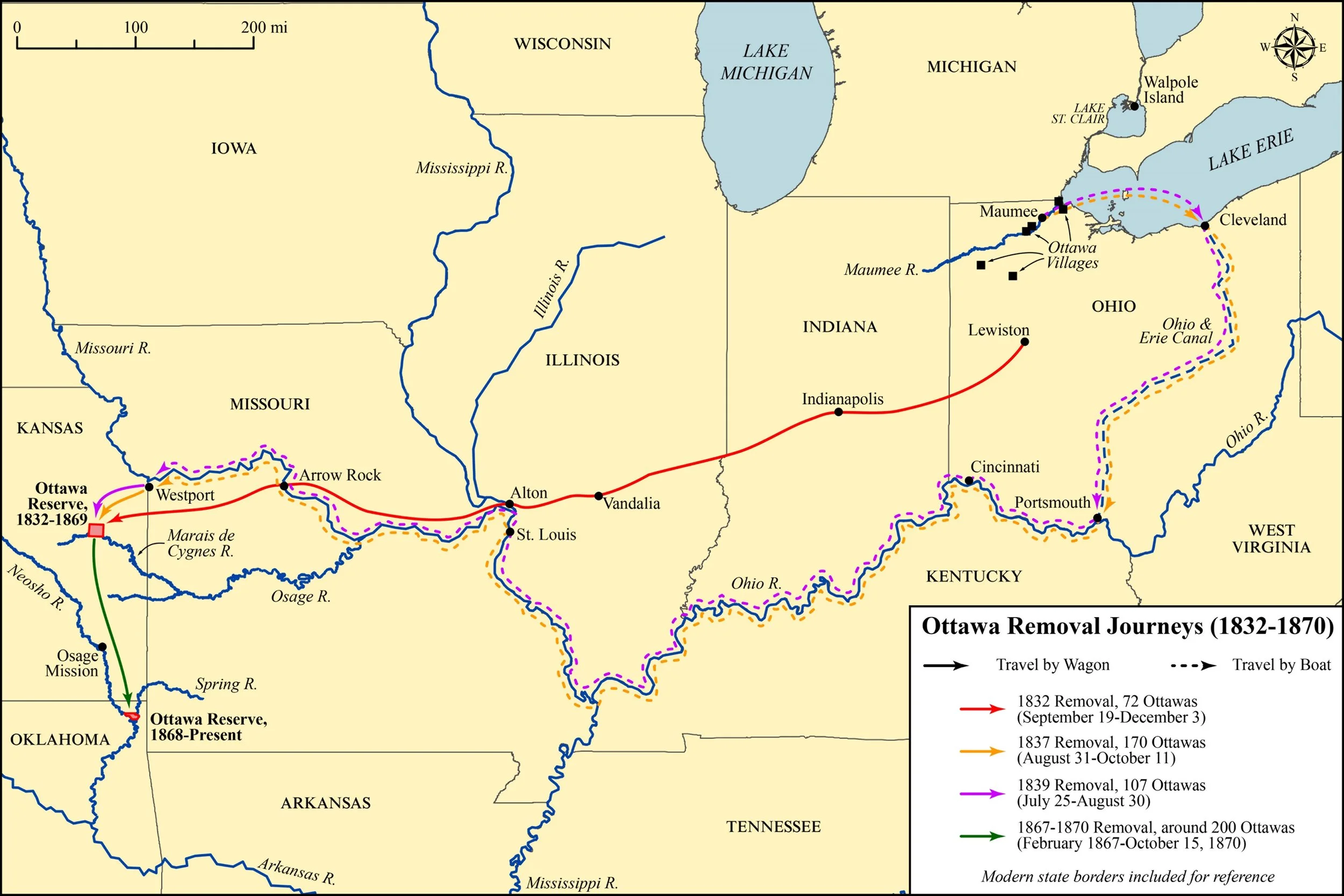

With the organization of the Kansas Territory in 1854, the Ottawa Tribe faced increasing pressure to give up their lands in Kansas and accept removal elsewhere. Having already suffered removal from Ohio and labored to build thriving farms in Kansas, the Ottawas vehemently opposed a further removal. Through an 1862 Treaty, the Ottawa consented to allotment and U.S. citizenship as alternatives to removal, and the Ottawas endowed land to establish a school as a means to navigate American society on their own terms.

Despite the treaty promises, Indian agent C.C. Hutchinson and other designing parties worked to dispossess the Ottawas of their selected allotment and school lands. Ottawa Chief John Wilson contended the Ottawas had been “swindled out of every right and interest which we have been taught the Treaty[of 1862] guaranteed to us.” Faced with the specter of near complete dispossession, Wilson began negotiations with the Shawnee Tribe to purchase part of their reservation in Indian Territory as a new tribal homeland.

In 1865, an Ottawa scouting party consisting of William Hurr, John W. Earley, and James Wolfe journeyed to Indian Territory to assess the lands the Ottawas contemplated purchasing from the Shawnees. When the scouting party reached their proposed homeland, they witnessed a romp of otters playing in a mudslide along the Neosho River on the western border of the reserve. Tribal leaders took the incident as an auspicious omen. The Ottawa purchased a 14,860-acre reservation from the Shawnee, and this purchase was confirmed via an 1867 Treaty.

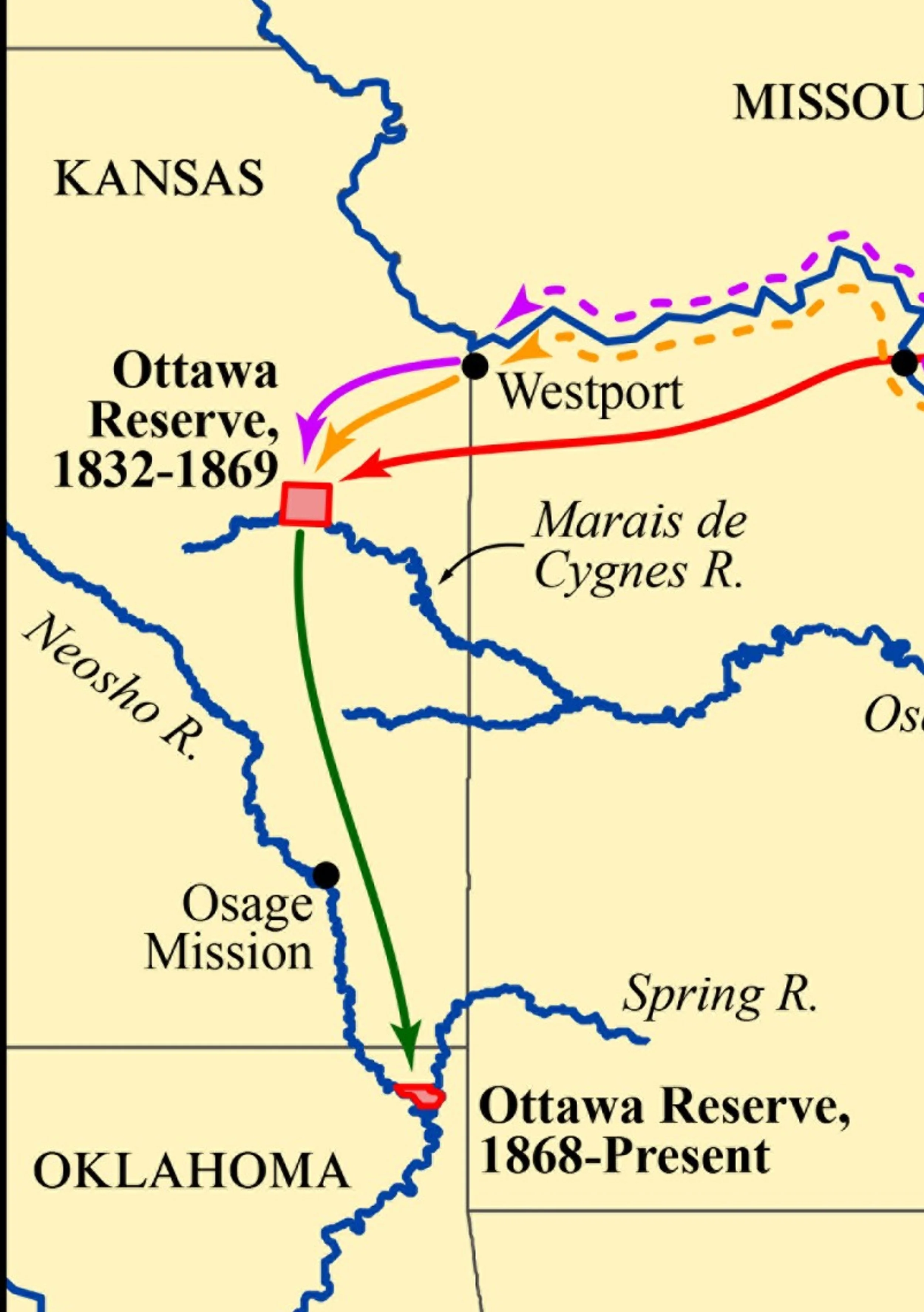

Removal from Kansas to Indian Territory took place mostly between 1867-1870 and featured small family groupings who made their way south after they sold their allotments and closed out their affairs in Kansas. Unlike removal from Ohio, federal officials did not supervise or manage removal.

Chief John Wilson, who led the effort to secure a new reservation in Indian Territory, never got to reside in the new tribal homeland. While on his way south, Wilson took ill and died at the Osage Mission, what is now Saint Paul, Kansas. His family carried his body the rest of the way, and he became the first person buried in what became the Ottawa Indian Cemetery.

The years immediately following removal were deadly and traumatic. Guy Jennison, whose mother survived the journey from Kansas, reflected on those difficult years: “the majority of the Tribe landed here with practically nothing. A few had a little money left from the sale of their lands in Kansas…The Ottawas scarcely raised anything. It got so dry that both rivers, Neosho and Spring River, stopped flowing. Shawnee Lake, east of (what is now) Miami, where all those water lilies used to be before Grand Lake was built, also went dry. For a vegetable, the Indians would go and dig down and get those tubers of the water lily. Something like a sweet potato and they cooked and ate them. The Old Indians said that they would have starved had it not been for them.” In addition to malnourishment, diseases plagued the Ottawas, and a particularly cold winter in 1870-1871 made matters worse. Joseph Badger King, chief in the years immediately after removal, estimated around half of the Ottawas died within a few years of moving to Indian Territory